|

If you're a poor child, the moment your family crosses this border heading north

the odds that you will be taken from your parents more than double. |

●

How did Massachusetts wind up tearing apart families at a rate more than 60%

above the national average - and two to three times the rate of Connecticut?

●

Why does Massachusetts also institutionalize children at a rate 60% above the

national average?

●

Why does Massachusetts have one of the worst records of racial disparity when

it comes to tearing apart Hispanic families?

This

post is adapted from a virtual presentation I gave last month to the Racial

Justice Task Force of the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services,

Child and Family Law Division.

Forty-three years ago, I started work as a

reporter for a public television station in Western Massachusetts. Whenever anyone in state government was asked

about the problems in the state’s “child welfare” system they’d give the same

stock answer: As soon as the new Department of Social Services was up and

running, and took over jobs then done by the Department of Public Welfare,

everything would be fine!

Today the Department of Public Welfare is

the Department of Transitional Assistance.

The Department of Social Services got itself a new name as well:

Department of Children and Families. On

the Massachusetts “child welfare” Titanic, there always are more deck chairs to

rearrange.

What has not changed in all of this is the

fanatical devotion of Massachusetts public officials – and private agencies –

to tearing apart families. That history

goes back well over a century.

While researching my book on family policing, I read an invaluable history, Heroes of Their Own Lives, by Linda Gordon. It traced the history and documented the

racism that infused the work of the Massachusetts Society for Prevention of

Cruelty to Children. Here’s some of what

she wrote:

MSPCC agents in practice and in rhetoric expressed disdain for

immigrant cultures. They hated the garlic and olive oil smells of Italian

cooking and considered this food unhealthy (overstimulating,

aphrodisiac). … [T]hey believed that women who took spirits were degenerate and

unfit as mothers. They associated many of these forms of depravity with

Catholicism. Agents were also convinced of the subnormal intelligence

of most non-WASP and especially non-English-speaking

clients; indeed, the agents' comments and expectations in this early

period were similar to social workers' views of

black clients in the mid-twentieth century….

Black women were described as “primitive,” “limited” …”fairly good for

a colored woman.” White immigrants came in

for similar abuse: e.g. “a typical low-grade Italian woman” [Others were

called] “typical Puerto Ricans who loved fun, little work and were dependent

people.”

That last remark appears in a

record from 1960.

When MSPCC agents felt their power

was insufficient, they bent or broke the law.

When SPCC agents couldn’t get into a home legally

They

climbed in windows, They searched without warrants. Their case notes frequently

revealed that they made their judgments first and looked for evidence later. …

As

one annual report put it delicately: “It is true we have taken risks on the

margin of legal liability which seemed needful to rescue the child … but

without cost to the society … If ‘indiscreet zeal’ which is made such a bugbear

occasionally leads us into mistakes, the public will condone the error … much

more readily than they would approve the opposite fault of timidity or

lukewarmness in cases of well-ascertained cruelty.”

In other words, as the current

Massachusetts “Child Advocate” Maria Mossaides

might say, they were “erring on the side of the child.”

Now let’s flash forward to

1989. While researching my book, I

interviewed a group of stewards for the caseworkers’ union in

Massachusetts.

This is some of what they told me:

“I work out of a very affluent area,”

said Brett Cabral. “We screen in [for investigation] … things that Boston would

be laughing at the person phoning in the report.”

“Don’t get investigated in Weymouth,”

said Robert Moro. “They’re famous for substantiating everything and naming

everybody.”

Said Philip Leduc, a veteran supervisor

in Northampton: “If the level of intrusiveness perpetrated allegedly to

protect children were attempted in any other field, we would be in court … we

would be in jail, we would have the Supreme Court coming down with innumerable

decisions against us.”

Or, as Moro put it: “Maybe we’re just too

damn intrusive.”

Now, let’s consider where we are today. In a moment, I’ll compare Massachusetts to

the national average, but first I want to emphasize: The national average

stinks. There are places across the

country that have proven children can be taken away at far lower rates than the

national average, with no compromise of safety.

So a comparison to the national average understates how bad things are

in Massachusetts.

Here’s the bottom line: No matter how you

slice and dice the data, Massachusetts is fanatical about tearing apart

families.

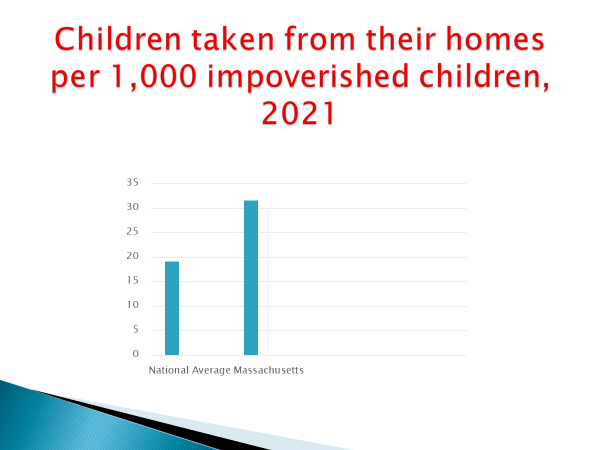

So in 2021, the most recent year for

which data are available, when you compare entries into care to impoverished

child population, Massachusetts tore apart families at a rate 60% above the

national average.

The snapshot number – the number of

children trapped in foster care on any given day -- is even worse. Massachusetts children were trapped in foster

care at a rate 65% above the national average.

And DCF has a fondness for putting

children in the worst possible placement – institutionalizing them in

“congregate care.” Massachusetts

institutionalizes children, at a rate 60% above the national average. Now, let’s see how racism comes into

play.

Nationwide, Black children represent

14% of the child population – but 23% of the foster child population.

In Massachusetts, the disparity is similar. Black children are nine percent of the total

child population and 15% of the foster child population.

However, the picture worsens when you add in

multi-racial children. The federal government data source does not appear to

have such a category online, but for Massachusetts, multi-racial children are

four percent of the child population – and nine percent of the foster child

population.

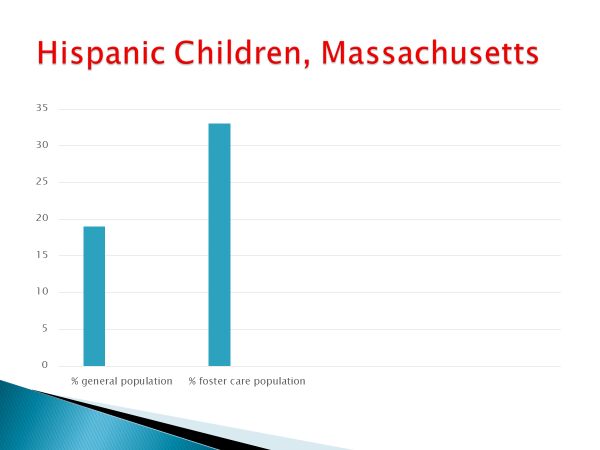

Nationwide, on average, Hispanic

children are not overrepresented in foster care. But in Massachusetts, they represent 19% of

the child population and 33% of the foster child population.

Someone who lived in Massachusetts

for only a short time, as I did, might think that bias against Native American

families would not be a problem, because the Native American population in

Massachusetts is low. But that would be

underestimating DCF!

A study of America’s 20 largest counties found that the county where Native American

children are most likely to be subjected to the trauma of a child abuse

investigation is: Middlesex County, Massachusetts. The county where Native American children are

second most likely to have their rights to their parents terminated also is

Middlesex County, Massachusetts.

There are only about 4,800 Native

Americans in the county, but by God, DCF seems to have its eye on all of

them! Fully half of Native American

children in that county will have to endure all the trauma of a child abuse

investigation.

The percentage for Black children enduring

traumatic investigations by DCF probably is even higher – since we know that nationwide, 53% of Black children will have to endure such

trauma and, as we’ve seen, Massachusetts almost always is worse than the

national average.

Connecticut

does better

Massachusetts’ record looks even

worse when you compare to a neighboring state with similar problems:

Connecticut. The rate of removal in

Massachusetts – again, factoring in poverty – is between double and triple the

rate in Connecticut.

Connecticut has not done well at

getting children out of foster care – so their snapshot number is very slightly worse than

the national average – but still way better than Massachusetts.

Connecticut fails on another count: though

it tears apart fewer families, period, the racial disparities are disturbingly

similar to Massachusetts.

But Connecticut does better than the

national average when it comes to institutionalizing children – they

institutionalize them at about half the rate in Massachusetts.

The Connecticut comparison on

overall removals is particularly relevant since it touches on the current

all-purpose excuse for the take-the-child-and-run mentality in Massachusetts: Opioids.

Opioid abuse didn’t stop at the

state line. But while Massachusetts

politicians and journalists spent their time demonizing parents, especially

mothers, who used drugs, Connecticut invested in one of the nation’s most

innovative home-based family drug treatment programs.

But that wasn’t even the biggest

reason for the difference. The biggest difference is leadership. In 2011, then-Gov. Dannel Malloy named Joette

Katz to run that state’s DCF. Not long

after, there was a high-profile child abuse death. There were all the usual calls for tearing

apart more families. Katz did something

simple.

She said no.

She made clear she wouldn’t tolerate

foster-care panic, that sharp sudden surge of removals of children that often

follows horror story cases. And Malloy

backed her up.

So far, their respective successors

in Connecticut are showing the same strong leadership.

Massachusetts, of course, has taken

a different approach. DCF has no

leader. Oh, it has a commissioner, but

it has no leader. And, like his

long-ago predecessors at the MSPCC, the governor has used every opportunity to

smear families and promote the Big Lie of American child welfare, that family

preservation and child safety supposedly are opposites.

So, in the wake of high-profile

child abuse fatalities – and demagogic news coverage from what was then the New

England Center for Investigative Reporting, the governor famously and falsely

claimed there was “mission confusion” at DCF – and somehow an agency which,

then as now, was tearing apart families at a rate far above the national

average was putting family preservation ahead of child safety.

A Boston Globe headline at

about the same time declared: “balance between children’s safety, family

stability is perennial challenge.”

And over and over, everyone from

Mossaides to lawmakers to newspaper editorials will give you some version of

“well, you know, we have to err on the side of the child.”

But it’s all a lie. Anything that equates child removal with

child safety is a lie. The only way to actually err on the side of the child is

to err on the side of the family. Because

it’s not just that family preservation is more humane than foster care; for the

overwhelming majority of children it is also safer than foster care.

That is because most cases are

nothing like the horror stories. Far more

common are cases in which poverty is confused with neglect.

There now have been at least six separate studies showing that in typical cases, children

left in their own homes typically fare better than comparably maltreated

children in foster care – even when the families don’t get any special

help. (Imagine what would happen if we

actually provided real help.)

That should come as no

surprise. The motivation of a DCF

caseworker in Holyoke and an ICE agent at the Mexican border may be different,

but the harm to a child torn from the arms of her or his mother is exactly the

same. Anyone who dares to use that “err

on the side of child” line needs to sit and listen to a recording of anguished cries of separated children at

the border, obtained by ProPublica. To

paraphrase activist Joyce McMillan: They tear apart families at the border of

Roxbury, too.

Once taken, children can be moved

from home to home, emerging years later unable to love or trust anyone. They have twice the level of post-traumatic stress

disorder of Gulf War

veterans. Only 20% are doing well in

later life. And they are more likely to wind up in prison than in college. How

is that “erring on the side of the child”?

But it’s not just a matter of

emotional abuse, enormous as that abuse is.

DCF wants you to believe that in any

given year only 1.59% of Massachusetts foster children are abused in foster

care.

Here’s what that means. They are claiming that if you filled a room

with 70 former foster youth and asked: “How many of you were abused during the

last year you were in foster care?” only one would raise her or his hand.

Of course, that’s absurd on its

face. But in case anyone seriously needs

research to confirm it, study after study after study has found abuse in one-quarter to one-third

of foster homes – and for a variety of methodological reasons, those estimates

almost certainly are low.

The rate of abuse in group homes and institutions

– which DCF loves so much – is even worse.

If a child is taken from a safe

home, or one that could be made safe, only to be beaten, raped or killed in

foster care -- recall, for example, Avelina Conway-Coxon -- how is

that “erring on the side of the child.”

But even that isn’t the worst of

it.

All that time spent on investigating

false allegations, trivial cases and poverty cases, all that time searching

homes and stripsearching children, all that time spent needlessly taking away

all those children is, in effect, stolen from finding the relatively few

children in real danger.

And that almost always is the real

reason for the horror stories that make headlines. How is that “erring on the side of the child”?

Reefer

madness at DCF

Then there’s the all-purpose excuse

for Massachusetts’ obscene rate of removal that I mentioned earlier: Opioids.

That, too, fails for several

reasons.

First, in more than two-thirds of

all Massachusetts cases, no substance abuse of any kind is even alleged.

Second, all substance use isn’t

opioids. There is no breakdown of how

often the substance at issue is one that is now legal in Massachusetts: marijuana. But we do know this: The referendum

legalizing marijuana in Massachusetts included language saying that marijuana

use alone could not be grounds for even a DCF investigation, let alone removal. DCF must have “clear,

convincing and articulable evidence that the person’s actions related to

marijuana have created an unreasonable danger to the safety of a minor child.”

That caveat is so mild that even

Mossaides didn’t object. But DCF threw a fit. The

referendum passed anyway so now the problem is solved – if, that is, you

believe DCF rigorously follows the law when it comes to intruding on

families.

The point here is that the talk

about drug abuse may say more about Massachusetts’ puritan tradition and reefer

madness at DCF, than actual danger to children.

Third, even in the case of opioids, a 2014 story hyping the opioid epidemic and parents

giving birth to children with drugs in their system, oh-so-briefly noted an

admission from Boston Medical Center.

They acknowledged that most of the infants born with drugs in their

system were exposed not to heroin, but to drugs like methadone or buprenorphine

– drugs medically prescribed to treat heroin

addiction.

None of that means opioid abuse is

not a serious and real problem. But even

in such cases, we should learn from a previous “worst drug plague ever” – crack

cocaine.

Researchers studied two groups of children born with cocaine in their systems; one

group was placed in foster care, another left with birth mothers able to care

for them. After six months, the babies

were tested using all the usual measures of infant development: rolling over,

sitting up, reaching out. Typically, the

children left with their birth mothers did better. For the foster children, the separation from

their mothers was more toxic than the cocaine.

Similarly, consider what The

New York Times found

when it looked at the best way to treat infants born with opioids in their

systems. According to the Times:

[A]

growing body of evidence suggests that what these babies need is what has been

taken away: a mother. Separating

newborns in withdrawal can slow the infants’ recovery, studies show, and

undermine an already fragile parenting relationship. When mothers are close at

hand, infants in withdrawal require less medication and fewer costly days in

intensive care.

“Mom is a powerful treatment,” said Dr.

Matthew Grossman, a pediatric hospitalist at Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital

who has studied the care of opioid-dependent babies.

It is extremely difficult to take a swing at

so-called “bad mothers” without the blow landing on their children. That

doesn’t mean we can always leave children with addicted parents. But it does mean that in most cases, even

when untreated parental drug use might endanger children, drug treatment for

the parent is a better option than foster care for the child.

Connecticut recognized that. The Puritans of Massachusetts DCF have not –

and neither has much of the Massachusetts media.

The

Betty Ford standard

Instead, Jennifer McKim’s reporting for the

New England Center – reprinted in the Boston Globe – echoed the worst

examples of “crack baby journalism” from the 1980s.

Her stories are replete with phrases

condemning parents “who caused their [infants’] drug problems in the first

place…” or a mother whose pregnancy “did not cause her to alter her daily

heroin habit…”

I doubt that McKim, or any other reporter,

would have spoken that way about the mom addicted to prescription opioids and

alcohol who raised her teenage children in an affluent neighborhood in

Alexandria, Virginia back in the 1970s.

And no family police agency investigated her when she moved to a new

residence in D.C. – the White House.

On the contrary, Betty Ford was treated as a

hero for admitting her addiction – and she wound up opening a celebrity rehab

center.

So let’s try applying the Betty Ford

standard to Black people, and Hispanic people, and Indigenous People and poor

white people.

One last thought about child welfare and

opioids. Massachusetts’ extreme outlier

status existed long before the opioid epidemic.

But that epidemic was well underway before a huge spike in children torn

from their homes that started in 2014 and continued through 2016 – in other

words, when the state’s awful record got even worse. That spike had nothing to do with opioids,

and everything to do with foster-care panic – the response by DCF to the demagoguery

that followed high-profile child abuse deaths.

But there are signs that, at last, some

people may be ready to reconsider the take-the-child-and-run approach that has

brought down so much misery on Massachusetts families – and made all children

less safe.

For a year, Mossaides stage-managed

presentations to her Massachusetts Mandatory Reporter Commission, in order to

persuade the commission to further expand mandatory child abuse reporting –

indeed, that was the commission’s charge.

But after hearing from affected families, practitioners, advocates and

scholars across the country, the Commission refused to buy what Mossaides was

selling. They refused to make any

recommendations at all. This was so

extraordinary that it recently gained national attention in a story by NBC News and ProPublica, which

documented the enormous harm mandatory reporting does to families.

Because there’s so much available

about this on our special mini-website about the Massachusetts Mandatory Reporter

Commission, I won’t repeat it here. But

lawmakers need to understand that mandatory reporting makes children less safe.

Yes, the lawmakers will be

upset. Some will say: “If we won’t have

mandatory reporting we’ll miss some cases.”

They need to understand that there is no system that will find every

case. But with mandatory reporting, you

actually miss more of those “real cases.” That’s because the cases or horrific abuse

that make headlines are needles in a haystack.

|

Nationwide, the blue represents the percentages of cases that are screened

out or determined to be false, the red is the percentage of "substantiated" neglect

(which often means poverty) and the green are the percentage of "substantiated"

abuse of any kind. |

Each time you expand mandatory reporting you make the haystack bigger,

further deluging DCF with false reports, trivial cases, and poverty cases. That

only makes it harder to find the needles – even as you inflict needless trauma

on tens of thousands of children.

Mandatory reporting also creates

serious cases of abuse. Because it makes

families afraid to seek help before cases become serious.

Then they may say: “Can’t we fix it

with ‘training’? I would say: But how

many times have we heard training proposed as a panacea? How many times has it

worked? If we had before you massive

evidence of the harm – and the racism – of stop-and-frisk policing, how many of

us would be satisfied if a police chief said: “Don’t worry, we’ll just provide

more ‘training’ about who to stop and how to frisk them”?

There is no such thing as training

that eliminates racial bias, or class bias.

And even if there were – even the best-trained mandatory reporter may

have to ignore the training rather than risk fines or jail time for not

reporting.

That’s why creating some kind of

second hotline to report families who just need help won’t work either – unless

you also eliminate mandated reporting.

Eliminating mandatory reporting is

not the same as eliminating reporting.

Professionals would remain free to exercise their professional judgment

and call DCF whenever they genuinely believe it’s essential.

Like the rest of us, lawmakers have grown

up on a steady diet of “health terrorism” – the misrepresentation of the true nature

and scope of “child abuse” in the name of “raising awareness.” So of course abolishing mandatory reporting

would be a tough step to take, even though it will make Massachusetts children

safer.

But at a minimum lawmakers should be

willing to eliminate one of the worst aspects of mandatory reporting –

requiring people who work with survivors of domestic violence to turn those

survivors in to DCF if the children saw them being beaten, leaving the survivors

open to “failure to protect” allegations.

Taking children from battered

mothers is illegal in New York City, thanks to a class-action lawsuit. It still happens, of course, but it happens

less. My group’s Vice President was

co-counsel for the plaintiffs. During

the trial, one expert after another said the same thing: Witnessing domestic

violence can be emotionally harmful for a child. But taking the child from the

non-offending parent is far, far worse.

One expert said taking a child under such circumstances is “tantamount

to pouring salt into an open wound.”

The policy of DCF, and the approach

of Maria Mossaides, boils down to: “Please pass the salt.”

There are superb resources about

this specific to Massachusetts in the detailed written testimony to the Mandatory

Reporter Commission from Jane Doe, Inc., in the spoken testimony of attorney Michelle Lucier and in a recent Western New England Law Review article.

Long ago, the father of family

defense (and the president of NCCPR), Prof. Martin Guggenheim, said: “There is

a lot of hate disguised as love in this system.” Nothing better illustrates the point than the

fact that Maria Mossaides and DCF refused to consider something as minimal as

exempting those who deal with victims of domestic violence from mandatory

reporting laws.

Another issue on the horizon concerns

how children are represented in court. Mossaides

is trying to, in effect, silence children by undermining what’s known as -- expressed

wishes representation – that is, requiring children’s lawyers to fight for what

their child clients want. Mossaides is

exploiting a horror story, the death of Harmony Montgomery, to try to undermine that – even though the real lesson from that

tragedy is that Harmony probably never should have been taken from her mother

in the first place.

A

final note about names

I began by noting how often

Massachusetts family policing agencies change their organizational structure –

or even change their names. But if the

Massachusetts family police were honest they’d simply adopt the name used by

poor people more than a century ago to describe the Massachusetts Society for

the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Just call yourselves what you really are: “The Cruelty.”