Between 2019, before the pandemic, and 2023 foster care went down…

...and child safety improved

% ALLEGEDLY SUBJECT TO REPEAT “MALTREATMENT”

Here’s what happened: The family police (a more accurate term than “child protective services”) were forced to step back, community-run community-based mutual aid organizations stepped up and the federal government stepped in with the best “preventive service” of all, no-strings-attached cash. The result: A dramatic reduction in needless family surveillance and foster care with no compromise in safety. Even the head of the city’s family police agency at the time admitted it. Other studies, including one in JAMA Pediatrics, would confirm it.

But, the fearmongers replied: It’s still early! Just wait until 2021, when the kids are coming back to school. But in 2021, the federal government’s annual Child Maltreatment report found that what family police agencies label “abuse” and “neglect” reached a 30-year record low.

Oh, well, OK, the fearmongers said, just wait ‘till 2022! Then you’ll see how all those overwhelmingly poor disproportionately nonwhite parents treated their children because, after all, you know how they are, right?

Wrong. Data for 2022 from Pennsylvania and New York City showed there still was no surge in what agencies call “child abuse” and “neglect.”

I don’t know if the fearmongers are desperate enough to tell us that the “surge” in child abuse will happen in 2023 – but it looks like they’re wrong again.

New York City just released its annual Mayor’s Management Report for the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2023

So let’s compare 2019, the last fiscal year entirely

unaffected by COVID, to 2023:

INVESTIGATIONS + INVESTIGATIONS NOT LABELED AS INVESTIGATIONS, BUT STILL INVESTIGATIONS:

Note that these figures combine formal investigations with cases that are investigations in all but name. New York City’s family defenders have found that the city’s version of “differential response” can be even more intrusive than an investigation that’s labeled an investigation.

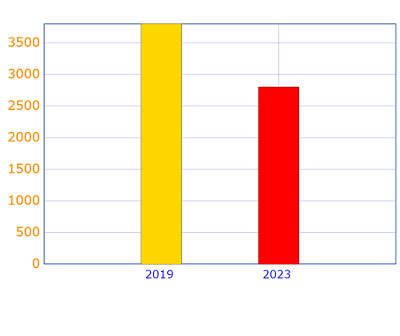

There’s a similar pattern when it comes to children forced into foster care. The number declined significantly, then there was regression. But the 2023 figure, 2,798, remains more than 25 percent lower than the number in 2019 when the city took 1,000 more children.

The safety measures

But, of course, the fearmongers want you to believe that

this modest reduction in family policing must have left children less safe.

There are two standard measures of child safety. One is foster-care “recidivism,” that is, of all children sent home from foster care what percentage are returned to foster care within a year? In 2023 8.5% of foster children sent home returned to foster care. That’s up from 7.5% in 2022 – but still well down from the 9.8% in 2019.

This also is potentially the more volatile of the two measures since the raw numbers are relatively low. A one percentage point difference, whether up or down, probably represents fewer than 18 children, since 1,770 foster children were reunified in FY 2022 – and we’re looking at what happened in the year that followed.

The second measure involves far more children: It concerns alleged recurrence of abuse or neglect – that is, the proportion of children for whom a caseworker checked the box declaring an allegation “indicated” for whom there was another “indicated” report within a year. That figure plummeted during COVID – and stayed down, falling from 17.9% in 2019 to 13.6% in 2023.

As we’ve noted previously, in 2022, New York raised the threshold for indicating a case to “preponderance of the evidence,” the abysmally low standard used in most states; incredibly it used to be even lower. That might account in part for the lower rate of alleged recurrence of “maltreatment.” But the dramatic decline in recurrence also could be seen in 2020 and 2021. Again, the pandemic-of-child-abuse thesis was that, in the absence of mandated reporters and the family police, abuse would skyrocket – and we’d see it when we got back to normal.

That didn’t happen.

Whether this progress can be maintained is an open question. That extra cash assistance is no longer going to poor families – resulting in a dramatic rise in child poverty nationwide. It’s not as if ACS ever stopped confusing poverty with neglect; so more poverty means a more target-rich environment for ACS. And, of course, at any time a child abuse death could prompt a demagogic reaction from politicians creating the risk of a foster-care panic, a sharp sudden increase in needless removals of children. How would ACS respond to that? The current leader, Jess Dannhauser, has yet to be tested.

If we really want to keep making children safer a good start would be for the state and the city to step in and replace the cash assistance the federal government no longer provides – or at least provide no-strings-attached funds to the mutual aid organizations that sprang up during the pandemic.

And remember, this progress comes in a place that, even before COVID had a terrible system, but a less terrible system than most. Wherever you are, it’s all probably worse.